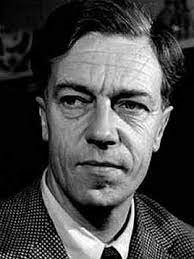

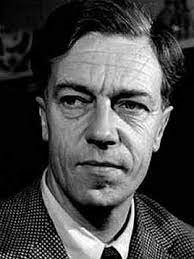

To mark the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the death of Cecil Day-Lewis on May 22nd 1972

Professor Albert Gelpi celebrates Cecil Day-Lewis with an introduction to a special selection of his poems.

[Albert Gelpi is the William Robertson Coe Professor of American Literature emeritus, at Stanford University. He and Day-Lewis became friends during Day-Lewis’s year at Harvard as the Norton Professor of Poetry. He wrote a critical study of Day Lewis’s poetry, Living in Time (1998), and edited, with Bernard O’Donoghue, a volume of Day-Lewis’s prose, The Golden Bridle (2017).]

C. DAY-LEWIS (1904-1972)

THE CONFLICT

The poems that Day-Lewis published during the Thirties—especially in The Magnetic Mountain (1933) and A Time to Dance (1935)– made him the most politically engaged of the Oxford poets. But what gave those poems a dramatic edge and urgency was the record of his personal effort to become a revolutionary poet by imagining a world beyond the ingrained values of his class and education.

I sang as one

Who on a tilting deck sings

To keep men’s courage up, though the wave hangs

That shall cut off their sun.

As storm-cocks sing,

Flinging their natural answer in the wind’s teeth,

And care not if it is waste of breath

Or birth-control of spring.

As ocean-flyer clings

To height, to the last drop of spirit driving on

While yet ahead is land to be won

And work for wings.

Singing I was at peace,

Above the clouds, outside the ring:

For sorrow finds a swift release in song

And pride its poise.

Yet living here,

As one between two massive powers I live

Whom neutrality cannot save

Nor occupation cheer.

None such shall be left alive:

The innocent wing is soon shot down,

And private stars fade in the blood-red dawn

Where two worlds strive.

The red advance of life

Contracts pride, calls out the common blood,

Beats song into a single-blade,

Makes a depth-charge of grief.

Move then with new desires,

For where we used to build and love

Is no man’s land, and only ghosts can live

Between two fires.

O DREAMS, O DESTINATIONS: 9

Day-Lewis recognized “the riddle of identity” as a recurrent and pressing theme of his work. This concluding poem in this sequence from Word Over All (1943) uses the sonnet structure deftly to pose and seek to resolve the riddle in terms of the simultaneous desire for freedom and commitment, openness and closure, or, as he phrased it elsewhere, the tension between the “need for roots with a craving to be unrooted.”

To travel like a bird, lightly to view

Deserts where stone gods founder in the sand,

Ocean embraced in a white sleep with land;

To escape time, always to start anew.

To settle like a bird, make one devoted

Gesture of permanence on the spray

Of shaken stars and autumns; in a bay

Beyond the crestfallen surges to have floated.

Each is our wish. Alas, the bird flies blind,

Hooded by a dark sense of destination:

Her weight on the glass calm leaves no impression,

Her home is soon a basketful of wind.

Travellers, we’re fabric of the road we go;

We settle, but like feathers on time’s flow.

THE HOUSE WHERE I WAS BORN

Day-Lewis was born in the west of Ireland where his father was pastor of a parish. He has remarked that “though I did write some ‘war poems’ in 1935-45, the main effect upon me of the emotional disturbance of the war was that, for the first time in my life I was able to use in poetry my memories of childhood and adolescence.” This poem appeared in Pegasus (1957), and meditations on his Anglo-Irish heritage became an increasing concern, culminating in the last volume published during his lifetime, The Whispering Roots (1972). Queen’s County is now Co. Laois..

An elegant, shabby, white-washed house

With a slate roof. Two rows

Of tall sash windows. Below the porch, at the foot of

The steps, my father, posed

In his pony trap and round clerical hat.

This is all the photograph shows.

No one is left alive to tell me

In which of those rooms I was born,

Or what my mother could see, looking out one April

Morning, her agony done,

Or if there were any pigeons to answer my cooings

From that tree to the left of the lawn.

Elegant house, how well you speak

For the one who fathered me there,

With your sanguine face, your moody provincial charm,

And that Anglo-Irish air

Of living beyond one’s means to keep up

An era beyond repair.

Reticent house in the far Queen’s County,

How much you leave unsaid.

Not a ghost of a hint appears at your placid windows

That she, so youthfully wed,

Who bore me, would move elsewhere very soon

And in four years be dead.

I know that we left you before my seedling

Memory could root and twine

Within you. Perhaps that is why so often I gaze

At your picture, and try to divine

Through it the buried treasure, the lost life—

Reclaim what was yours, and mine.

I put up the curtains for them again

And light a fire at the grate:

I bring the young father and mother to lean above me,

Ignorant, loving, complete:

I ask the questions I could never ask them

Until it was too late.

SHEEPDOG TRIALS IN HYDE PARK

Dedicated to Robert Frost, a poet Day-Lewis admired second perhaps only to Thomas Hardy, this poem commemorates his taking Frost to the trials during the latter’s visit to England in 1957. The description, from The Gate (1962), illustrates Day-Lewis’s skill in writing conversational speech into rhyme and meter as it turns free play within the rules and conventions of the trials into an elaborated metaphor for the poetic process itself.

A shepherd stands at one end of the arena.

Five sheep are unpenned at the other. His dog runs out

In a curve to behind them, fetches them straight to the shepherd,

Then drives the flock round a triangular course

Through a couple of gates and back to his master: two

Must be sorted there from the flock, then all five penned.

Gathering, driving away, shedding and penning

Are the plain words for the miraculous game.

An abstract game. What can the sheepdog make of such

Simplified terrain?– no hills, dales, bogs, walls, tracks,

Only a quarter-mile plain of grass, dumb crowds

Like crowds on hoardings around it, and behind them

Traffic or mounds of lovers and children playing.

Well, the dog is no landscape-fancier; his whole concern

Is with his master’s whistle, and of course

With the flock– sheep are sheep anywhere for him.

The sheep are the chanciest element. Why, for instance,

Go through this gate when there’s on either side of it

No wall or hedge but huge and viable space?

Why not eat the grass instead of being pushed around it?

Like a blob of quicksilver on a tilting board

The flock erratically runs, dithers, breaks up,

Is reassembled: their ruling idea is the dog;

And behind the dog, though they know it not yet, is a shepherd.

The shepherd knows that time is of the essence

But haste calamitous. Between dog and sheep

There is always an ideal distance, a perfect angle;

But these are constantly varying, so the man

Should anticipate each move through the dog, his medium.

The shepherd is the brain behind the dog’s brain,

But his control of dog, like dog’s of sheep,

Is never absolute– that’s the beauty of it.

For beautiful it is. The guided missiles,

The black-and-white angels follow each quirk and jink of

The evasive sheep, play grandmother’s-steps behind them,

Freeze to the ground, or leap to head off a straggler

Almost before it knows that it wants to stray,

As if radar-controlled. But they are not machines–

You can feel them feeling mastery, doubt, chagrin:

Machines don’t frolic when their job is done.

What’s needfully done in the solitude of sheep-runs–

Those rough, real tasks— become this stylized game,

A demonstration of intuitive wit

Kept natural by the saving grace of error.

To lift, to fetch, to drive, to shed, to pen

Are acts I recognize, with all they mean

Of shepherding the unruly, for a kind of

Controlled woolgathering is my work too.

WALKING AWAY

This poem for Day-Lewis’s eldest son Sean, also from The Gate, is one of his most popular and widely anthologized poems. The recollection of a seemingly casual and inconsequential moment turns into a gentle and wistful reflection on love’s attachments and detachments

It is eighteen years ago, almost to the day –

A sunny day with the leaves just turning,

The touch-lines new-ruled – since I watched you play

Your first game of football, then, like a satellite

Wrenched from its orbit, go drifting away

Behind a scatter of boys. I can see

You walking away from me towards the school

With the pathos of a half-fledged thing set free

Into a wilderness, the gait of one

Who finds no path where the path should be.

That hesitant figure, eddying away

Like a winged seed loosened from its parent stem,

Has something I never quite grasp to convey

About nature’s give-and-take – the small, the scorching

Ordeals which fire one’s irresolute clay.

I have had worse partings, but none that so

Gnaws at my mind still. Perhaps it is roughly

Saying what God alone could perfectly show –

How selfhood begins with a walking away,

And love is proved in the letting go.

ELEGY FOR A WOMAN UNKNOWN: II, III

The woman was Fiona Peters, whose husband Michael contacted Day-Lewis after her death from cancer in 1961 to tell him that his poems had sustained and inspired his wife through her long illness. The first section of this elegy, which appeared in The Room (1965), addresses her suffering and death. The second and third sections, presented here, open out, in metaphorical imagery derived from a Grecian trip in summer, 1962,into a meditation on life’s transience. On Delos, Day-Lewis “heard—almost as if the lions spoke it out of the island’s holy hush, ‘Not the silence after music, but the silence of no more music.’ To me those words had an extraordinary momentousness.” A stormy, windswept boat trip on the Aegean evoked the voyages of Odysseus and Aeneas (whose exploits in The Aeneid Day-Lewis had translated in the previous decade) and provided the impetus and imagery for the concluding section of the elegy.

II

Island of stone and silence. A rough ridge

Chastens the innocent azure. Lizards hang

Like their own shadows crucified on stone

(But the heart palpitates, the ruins itch

With memories amid the sunburnt grass.) Here sang

Apollo’s choir, the sea their unloosed zone.

Island of stillness and white stone.

Marble and stone— the ground-plan is suggested

By low walls, plinths, lopped columns of stoa, streets

Clotted with flowers dead in June, where stood

The holy place. At dusk they are invested

With Apollonian calm and a ghost of his zenith heats.

But now there are no temples and no god:

Vacantly stone and marble brood.

And silence— not the silence after music,

But the silence of no more music. A breeze twitches

The grass like a whisper of snakes; and swallows there are,

Cicadas, frogs in the cistern. But elusive

Their chorusing— thin threads of utterance, vanishing stitches

Upon the gape of silence, whose deep core

Is the stone lions’ soundless roar.

Lions of Delos, roaring in abstract rage

Below the god’s hill, near his lake of swans!

Tense haunches, rooted paws set in defiance

Of time and all intruders, each grave image

Was sentinel and countersign of deity once.

Now they have nothing to keep but the pure silence.

Crude as a schoolchild’s sketch of lions

They hold a rhythmic truth, a streamlined pose

Weathered by sea-winds into beasts of the sea,

Fluent from far, unflawed; but the jaws are toothless,

Granulated by time the skin, seen close,

And limbs disjointed. Nevertheless, what majesty

Their bearing shows— how well they bear these ruthless

Erosions of their primitive truth!

Thyme and salt on my tongue, I commune with

Those archetypes of patience, and with them praise

What in each frantic age can most incline

To reverence; accept from them perfection’s myth—

One who warms, clarifies, inspires, and flays.

Sweetness he gives, but also, being divine,

Dry bitterness of salt and thyme.

The setting sun has turned Apollo’s hill

To darker honey. Boulders and burnt grass.

A lyre-thin wind. A landscape monochrome.

Birds, lizards, lion shapes are all stone-still.

Ruins and mysteries in the favouring dusk amass,

While I reach out through silence and through stone

To her whose sun has set, the unknown.

III

We did not choose the voyage.

Over the ship’s course we had little say,

And less over the ship. Tackle

Fraying; a little seamanly skill picked up on our way;

Cargo, that sooner or later we should

Jettison to keep afloat one more day.

But to have missed the voyage—

That would be worse than the gales, inglorious calms,

Hard tack and quarrels below. . .

Ship’s bells, punctual as hunger; dawdling stars;

Duties— to scrub the deck, to stow

Provisions, break out a sail: if crisis found us of one mind,

It was routine that made us so,

And hailed each landfall like a first-born son.

Figure to yourself the moment

When, after weeks of the crowding emptiness of the sea

(Though no two waves are the same to an expert

Helmsman’s eye), the wind bears tenderly

From an island still invisible

The smell of earth— of thyme, grass, olive trees:

Fragrance of a woman lost, returning.

And you open the bay, like an oyster, but sure there’ll be

A pearl inside; and rowing ashore,

Are received like gods. They shake down mulberries into

Your lap, bring goat’s cheese, pour

Fresh water for you, and wine. Love too is given.

It’s for the voyaging that you store

Such memories; yet each island seems your abiding-place.

.. . For the voyaging, I say:

And not to relieve its hardships, but to merge

Into its element. Bays we knew

Where still, clear water reamed like a demiurge

And we were part of his fathomless dream;

Times, we went free and frisking with dolphins through the surge

Upon our weather bow.

Those were our best hours— the mind disconnected

From pulsing Time, and purified

Of accidents; those, and licking the salt-stiff lips,

The rope-seared palms, happy to ride

With sea-room after days of clawing from off a lee shore,

After a storm had died.

Oh, we had much to thank Poseidon for.

Whither or why we voyaged,

Who knows?. . . A worst storm blew. I was afraid.

The ship broke up. I swam till I

Could swim no more. My love and memories are laid

In the unrevealing deep. . . But tell them

They need not pity me. Tell them I was glad

Not to have missed the voyage.

ON NOT SAYING EVERYTHING

During the academic year 1964-65 Day-Lewis was the Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard University. Musing on the tree outside the sitting room window of his residence at Lowell House grew into this “poem in praise of limitations—which I would leave as a last word.”

This tree outside my window here,

Naked, umbrageous, fresh or sere,

Has neither chance nor will to be

Anything but a linden tree,

Even if its branches grew to span

The continent; for nature’s plan

Insists that infinite extension

Shall create no new dimension.

From the first snuggling of the seed

In earth, a branchy form’s decreed.

Unwritten poems loom as if

They’d cover the whole of earthly life.

But each one, growing, learns to trim its

Impulse and meaning to the limits

Roughed out by me, then modified

In its own truth’s expanding light.

A poem, settling to its form,

Finds there’s no jailer, but a norm

Of conduct, and a fitting sphere

Which stops it wandering everywhere.

As for you, my love, it’s harder,

Though neither prisoner nor warder,

Not to desire you both: for love

Illudes us we can lightly move

Into a new dimension, where

The bounds of being disappear

And we make one impassioned cell.

So wanting to be all in all

Each for each, a man and a woman

Defy the limits of what’s human.

Your glancing eye, your animal tongue,

Your hands that flew to mine and clung

Like birds on bough, with innocence

Masking those young experiments

Of flesh, persuaded me that nature

Formed us each other’s god and creature.

Play out then, as it should be played,

The sweet illusion that has made

An eldorado of your hair

And our love an everywhere.

But when we cease to play explorers

And become settlers, clear before us

Lies the next need—to re-define

The boundary between yours and mine;

Else, one stays prisoner, one goes free.

Each to his own identity

Grown back, shall prove our love’s expression

Purer for this limitation.

Love’s essence, like a poem’s, shall spring

From the not saying everything.

At the suggestion of Professor Albert Gelpi and extracted from the Notes for Broadsheet series No.36 which appear in each issue of Agenda is the following essay by C.Day-Lewis.

from ‘Making a Poem’

‘The Gate’ is dedicated to Trekkie Parsons, the artist whose small landscape painting, Day-Lewis said, ‘held for me a special and mysterious meaning.’ This excerpt from a lecture from the mid-sixties, first published in The Golden Bridle: Selected Prose (2017), traces the genesis and development of the poem as it searches the painting and arrives at its secret epiphany.

I would like to illustrate with a poem of mine called ‘The Gate’. It is one of several written in a state of creative exhilaration stimulated by my first visit to the U.S.A. a few years ago. I have chosen it partly because its data (which are all given in the first six lines of the poem) were apparently simple and straightforward and were already contained within a frame; for the poem arose out of a picture, painted by a friend of mine – a picture to which I responded with pleasure and excitement, but also with a sense that it held for me a special and mysterious meaning I must try to explore through poetry.

The Gate

In the foreground, clots of cream-white flowers (meadow-sweet?

Guelder? Cow parsley?): a patch of green: then a gate

Dividing the green from a brown field; and beyond,

By steps of mustard and sainfoin-pink, the distance

Climbs right-handed away

Up to an olive hilltop and the sky.

The gate it is, dead-centre, ghost-amethyst-hued,

Fastens the whole together like a brooch.

It is all arranged, all there, for the gate’s sake

Or for what may come through the gate. But those white flowers,

Craning their necks, putting their heads together,

Like a crowd that holds itself back from surging forward,

Have their own point of balance— poised, it seems,

On the airy brink of whatever it is they await.

And I, gazing over their heads from outside the picture,

Question what we are waiting for: not summer—

Summer is here in charlock, grass and sainfoin.

A human event?— but there’s no path to the gate,

Nor does it look as if it was meant to open.

The ghost of one who often came this way

When there was a path? I do not know. But I think,

If I could go deep into the heart of the picture

From the flowers’ point of view, all I would ask is

Not that the gate should open, but that it should

Stay there, holding the coloured folds together.

We expect nothing (the flowers might add), we only

Await: this pure awaiting—

It is the kind of worship we are taught.

This poem was written more or less straight ahead: more often I compose a bit here, a bit there, like a painter. The first stanza objectively sets out the facts – the colour and detail of the pictured landscape. In the second stanza, the eye pans up to its dominant features – the flowers in the foreground, the gate in the centre focusing the whole landscape together. At this point I still had no idea why the picture had such attractive mystery for me, or what it was trying to convey. However, in this second stanza I concentrated upon its main features subjectively – the central mystery, and my sense that the foreground flowers stood in an attentive pose, waiting for something to happen.

But I still had not discovered the theme of the growing poem. So, in stanza three, I tried putting a number of questions to the picture: just what are the flowers, and myself the outside observer, waiting for? Several possible answers were given, and each of them in turn rejected; but the first seven lines are constructed out of this series of rejections, in such a way that their logical negatives create something emotionally positive. And then, at last, I saw what the landscape – and the poem – were saying to me. I saw it by moving from outside the picture and looking at the gate ‘from the flowers’ point of view.’ In my tiny way I had done what Copernicus did when, with a superb imaginative leap, leaving the earth and placing himself in the sun, he found that the orbits of the planets looked simpler from that point of view.

What the picture was saying to me, I discovered, is first that the flowers expect nothing, their task being one of ‘pure awaiting’, a kind of worship; and second, that they (and I) are not concerned with a divine revelation (the gate opening), but only that the gate should stay there – in other words, that we should retain the sense of some Power at the centre of things, holding them together. This idea is foreshadowed (line eight) in purely visual or aesthetic terms: it was not till I reached the final stanza that I became aware of its deeper significance and realized that the poem was a religious poem. It is also, obviously, the poem of an agnostic – one who is, in a sense, ‘outside the picture’ – but an agnostic whose upbringing was Christian: the ‘olive hilltop’, with its echo of Mount Olivet, may conceivably have started the poem in the religious direction which, unforeseen by me, it was to take; and the ‘ghost-amethyst’ colour of the gate certainly led me along to ‘The ghost of one who often came this way’, i.e. the once-felt presence of deity in the human scene.

A few technical points: the poem had no end-rhymes, but the two most important words in it rhyme and are repeated – ‘gate’ six times, ‘wait’ (‘await’, ‘awaiting’) four times. The stanzas are carefully organized, the first corresponding metrically with the last, the second with the third: the pause between third and fourth stanza, which should be observed in reading the poem aloud throws the greatest possible emphasis on ‘From the flowers’ point of view’, highlighting the change of position which is to reveal the theme. Finally, the rhythms are as flexible as I could make them, within a regular metre, so as to reflect the inquiring and tentative nature of the poem’s thought-process.

Talking about the poem in this detached way, I have given the impression perhaps that a poem ‘writes itself’. Nothing could be further from the truth – in my case, at any rate. Certainly, in the first phase of composition, the ‘fishing’ phase, the intellect is relatively inactive; one accepts, in a trance- like state, everything that comes up. But there follows a phase of the most arduous intellectual activity, when the gathered material has to be criticized in the light of the growing poem and of whatever inkling I may have about its theme. Since the two phases constantly overlap, it is almost impossible to give a blow-by-blow commentary on the making of a poem. All I can say is that my mind moves gradually over from passive to active, as it tries to per- form the two functions of making and of exploring.

© Estate of C.Day-Lewis